The ability to make hard decisions, cope with difficult situations and persevere through extraordinary challenges without suffering from mental injury is what I mean when I talk about being mentally tough. Mental Toughness isn’t about being macho, uncaring, or self-centred, rather it’s about having grit, determination, resolve, and being confident that you can prevail, even if the odds are stacked against you.

Mental toughness is a personality trait that can be developed through training and employing techniques that callus the mind and condition you to not be impacted by situational factors. Mental toughness is an essential condition for leaders and anyone wanting to succeed in life. Individuals with high levels of mental toughness are better equipped to handle stress and pressure, make sound decisions under challenging circumstances, and maintain their motivation and focus. They are also less likely to be coerced by external emotive influences or allow their own emotions to hijack their judgment or diminish their motivation.

The American sports psychologist Dr. Jim Loehr was the pioneer of mental toughness as a concept. Dr. Loehr, worked with the Human Performance Institute and conducted research into the mental toughness of athletes, looking at how mindset and mental toughness affected their performance. Dr. Loehr may have been the first person to combine academic research on the topic with its practical application through sport to prove that positive outcomes can be achieved through focus and practice.

Professor Peter Clough, Keith Earle, and Doug Strycharzcyk, expanded on Dr. Loehr’s work believing mental toughness has a much broader application than just in sports. Their definition of mental toughness is:

“The personality trait which determines in large part how people deal effectively with challenges stressors and pressure, irrespective of circumstances.”

They also developed a mental toughness model comprising four components, the 4C’s of Control, Commitment, Challenge, and Confidence.

I fear one of the greatest challenges we will face in the ‘west’ this century, is the steady decline of mental toughness, especially in our young people who face the daunting threats of future pandemics, climate change, a third world war, and the regressive impact of a new global socialist world order.

Our capacity to endure stress and situational factors that challenge our resilience and our resolve is our level of mental toughness.

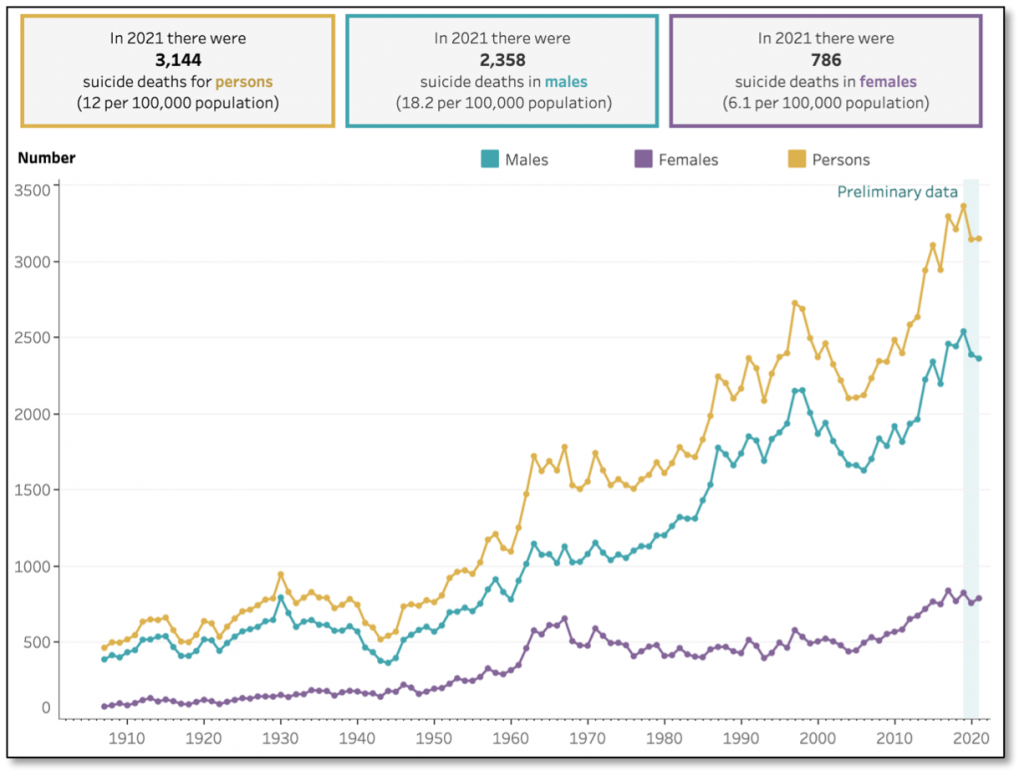

The number of suicides in Australia has risen steeply over the past 100 years or so as shown in Figure 1 below, with an interesting dip for males during the height of WWII. I should note that population has played a large part in the increase in the number of suicides; however, the rate of suicides per 100,000 population tells a surprisingly different story. I’ll come back to that later. Being mentally tough, can’t however, replace a missing purpose.

The statistics during WWII indicate the lowest number of male suicides in the past 100 years at 362 in 1944, there are likely several factors that would have affected the accuracy of records for wartime suicides. It’s possible that many men who may have committed suicide had there been no war, were killed in action, suicides may have been counted as war casualties, and statisticians may not have been able to accurately record the number of suicides given the scale and geographical span of our troops during the war and the volatile circumstances at the time.

Accepting that inaccuracy would likely have skewed the numbers to some degree, I want to offer another possible explanation. Men are protectors. They protect their families, their mates, their property, their values and beliefs, and they’ve tended, at least in the past, to be very patriotic and determined to uphold their way of life. Men will react aggressively to anyone or anything that threatens their loved ones, their beliefs, their country, or their way of life. Men will do this selflessly and will sacrifice themselves to protect what’s most precious to them. You could argue men are hard-wired to risk death protecting what’s important to them, including in the service of their nation.

As protectors, men also seem to have an almost innate need, to be needed, to have a purpose, and to put the needs of others ahead of their own. This is a form of self-sacrifice, which you could also argue is a somewhat suicidal tendency. In other words, men either die for a cause or die by their own hand if they don’t have a cause to die for.

So why cover suicide to this extent in a short passage on mental toughness? Well, we often assume that those who commit suicide are in some way mentally weak or damaged or they have demons lurking under the surface that drive them to it. This may well be true for many, but it doesn’t explain why less men committed suicide during the worse time, and arguably worse war, in the last 100 years. Could it be that men are less likely to commit suicide when they have a purpose, a challenge, something to strive for or to protect? Could it be men are more prone to committing suicide when these things are missing and when they have nothing to metaphorically ‘sacrifice’ themselves for?

This is not to diminish the impact that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has on those who make it through war, only to take their own lives once they return home. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), annual suicide monitoring report revealed at least 1,600 serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force (ADF) members died by suicide between 1997 and 2020, and there were 79 deaths by suicide in 2020.

The AIHW has compiled five suicide monitoring reports that revealed that ex-serving ADF members are at significantly higher risk of dying by suicide than the civilian population. Ex-serving males are 27% more likely to die by suicide and ex-serving females are 107% more likely to take their own lives than their corresponding civilian male and female counterparts.

Men who leave the ADF for involuntary medical reasons are three times as likely to die by suicide than those who leave voluntarily. Surprisingly, current permanent and reserve males, that is, males who continue to serve, are about half as likely to die by suicide as other Australian males. Without diminishing the horrific experiences that many of these men endured during their operational service in the ADF, the fact that the suicide rate amongst those who continue to serve is half that of their civilian counterparts might indicate that continued service is in some way keeping them from taking their own lives.

It’s important to understand that there may be many other reasons for this, such as those who chose to continue to serve being from a very stable portion of the population with a very low tendency to commit suicide regardless of their continued service, although this would not seem to be what the data suggests. Anecdotally, those who continue to serve, have the support of their comrades and a shared purpose that keeps them going.

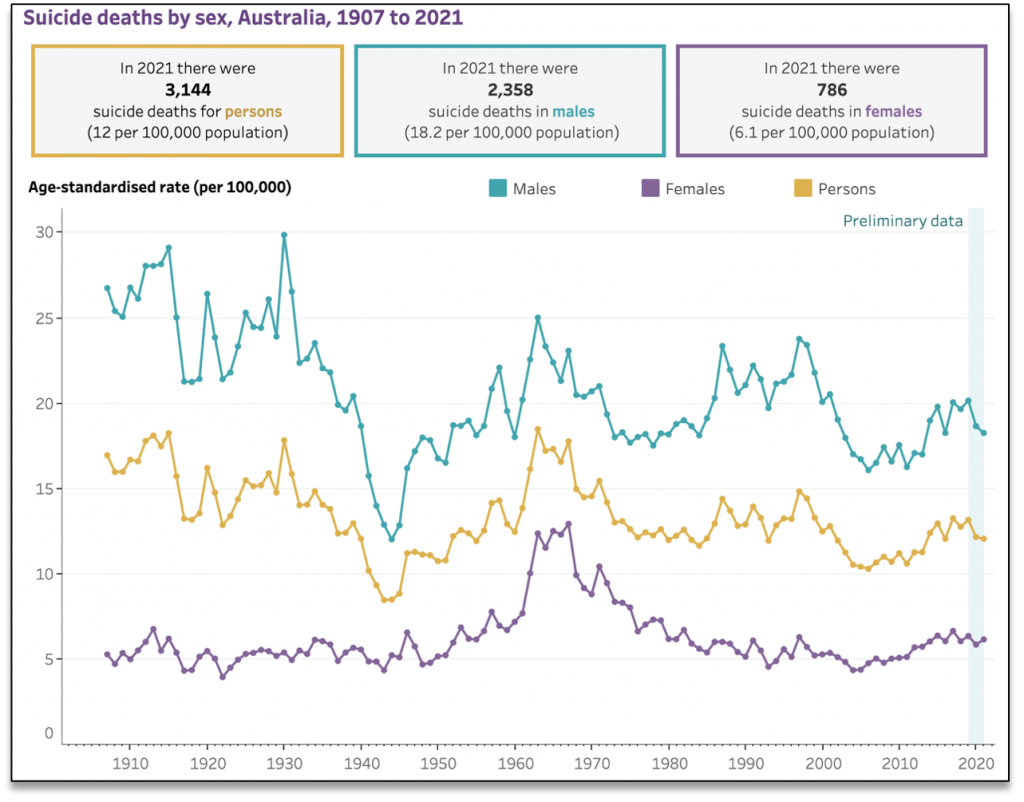

This is where I circle back to my statement that the “rate of suicides per 100,000 population tells a surprisingly different story”. This is because age-standardised percentage of suicides per 100,000 people has gone down slightly, not up! See figure two below.

My point in all of this is that I don’t see a clear connection between how mentally tough someone is and their likelihood of committing suicide; rather, I see a loss of purpose as being the key contributor.

Building mental toughness is what allows us to handle difficult challenges and life-altering setbacks and leads to increased confidence and self-esteem. We become more resilient and adaptable, able to bounce back from failure, allowing us to continue moving forward without suffering a mental injury. Mental toughness also enhances our ability to manage stress and anxiety, which will ultimately lead to improved mental health and overall well-being. This is important because life is hard, and we need to be conditioned to deal with it. Being mentally tough, can’t however, replace a missing purpose.