The saying “one size fits all” really doesn’t work when it comes to leadership. Afterall, we are all different and unique. We have different beliefs, values, abilities, motivations, and aspirations. So, as leaders, why do we assume we can lead everyone in the same way? We can’t.

Imagine you’re fresh out of school and it’s your first day at a new job. You have no real understanding of what your role requires of you and therefore no idea how to achieve the list of outcomes on your new position description, if you’re lucky enough to have one. You complete some notional induction training and tick off some items on a HR check list and then you’re off. Your new boss comes over to you and rattles off 10 lines of instructions with no context or explanation then disappears into his office. How do you think you will perform? Not great I bet.

Now imagine you have been working in your role for 10 years. You have completed multiple advanced training courses and regularly provide advice and guidance to more junior staff. What goes through your mind when your boss continuously insists on explaining what she needs you to do and how she requires you to do it? Pretty annoyed and undervalued I’d bet.

Now we’re somewhat conflating leadership with management here, after all its rare that you’ll be just a leader or a manager, can you see how each of these staff members have different needs and hence need to be led in different ways?

In 1969, researchers Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard created their ‘life cycle theory of leadership’ while working on Management of Organizational Behaviour. During the mid 1970’s the theory was renamed Situational Leadership Theory.

The origins of Situational Leadership stem from related research conducted at Ohio State University on what they referred to as the two-factor theory of leadership. The researchers postured that leadership styles are dependent on task behaviour and relationship behaviour.

In the early 1980s, Hersey and Blanchard both developed their own slightly divergent versions of the Situational Leadership Theory. Hersey developed the Situational Leadership Model while Blanchard expanded the theory and developed the Situational Leadership II model, in popular use today.

The fundamental principle of the situational leadership model is that there is no single style of leadership that is effective in every situation. To be effective, the leadership style used needs to be task-relevant, and the most successful leaders are those who can adapt their leadership style to the performance level of the individual or group they lead, in terms of their ability and willingness. Effective leadership varies, not only with the person or group being led, but also based on the task, job, or function that needs to be performed.

The Situational Leadership Model has two fundamental concepts: leadership style and the individual or group’s performance readiness level, also referred to as their development level.

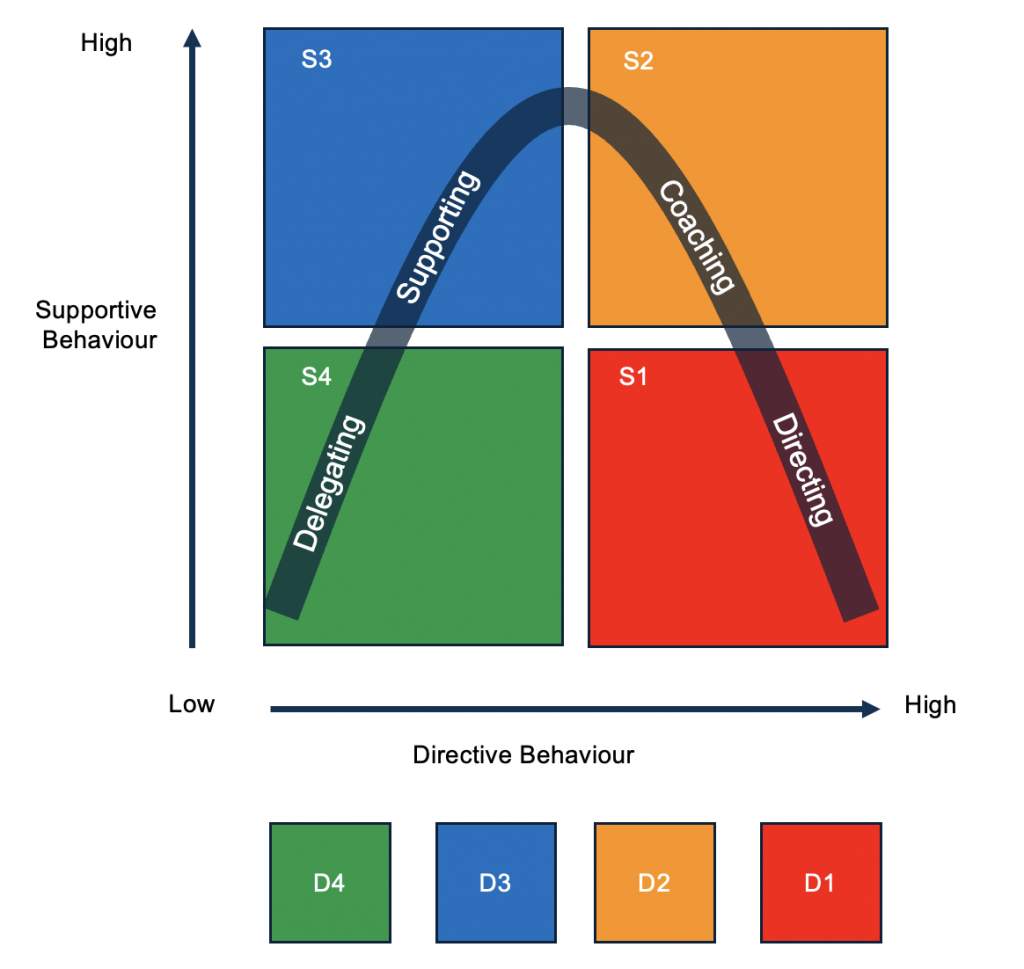

The figure below shows the relationship between the individual’s development level and the level of leader support they require.

As you move around the model, you’ll see that those at the Development Level 1 (D1), require the leader to demonstrate a high level of Directing Behaviour. That is to say that those who are new to a role, task, or scenario will need to be told what to do and how to do it and will require the highest level of support and direction compared to someone with much more training and experience.

As the individual gains more experience, they will move to Development Level 2 (D2), where the support they require from their leader is less directing and more coaching. At this level, the individual understands the principles of the task but lacks the full knowledge for how to complete the task on their own. At the D2 level the individual no longer needs to be told what to do but may need to be reminded how to perform certain aspects of the task. At this level the leader should promote more autonomy and lead by coaching the individual to recall their training and to put it into action. There may also be a need to confirm the training and even go back over certain aspects that may not have been fully understood.

Once the individual becomes competent, they may still lack the experience and confidence needed to function in a totally autonomous fashion. At this Development Level 3 (D3), the individual is capable of completing the task or performing their role, but may need reassurance, affirmation, and varying degrees of leader support.

At Development Level 4 (D4), the individual is highly competent and capable of completing the task or their role independently, with little or no direction. Here, the leader need only delegate the task and seek status reports on progress.

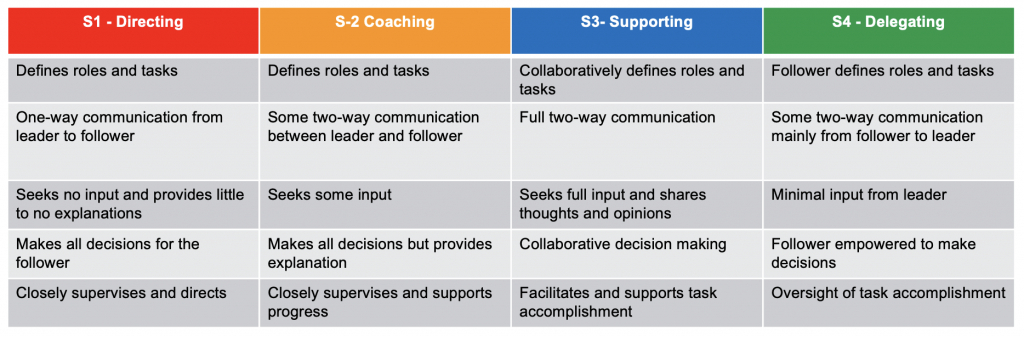

The basic directing and supporting behaviours for each Development Level are detailed in the table below. You will see how leaders can be seen to be ‘micromanaging’ their staff when they may be simply treating everyone as if they are stuck at Development Level 1 (D1).

Inversely, the busy leader who assumes their staff are all at Development Level 4 (D4), may seem to be absent and to be delegating or even abdicating their responsibilities, by staff who need their support.

This is a very brief overview of Situational Leadership Theory designed to stimulate thought and discussion. There are several criticisms of the theory with the main one being that it’s possible for individuals to be at a level D3 or D4 for some tasks while still being at a level D1 or D2 for others. The Leader would therefore need to have and maintain a very high degree of awareness of each individual team member’s Development Level and the amount of support they need. Situational Leadership is also difficult to apply to a team scenario when the individuals within the team are at different Development Levels.

Despite these and other criticisms, it is useful for leaders to know that each member of their team will likely be at different Development Levels and will therefore require different levels of support from Directing, to Coaching, Supporting and Delegating.

Once you are familiar with Situational Leadership Theory, you may find yourself spending more time observing those you lead, assessing their Development Levels, and trying to provide the support you feel they need. Be careful that you don’t attempt to implement Situational Leadership as a wholesale leadership style.

Having a basic knowledge of Situational Leadership Theory allows leaders to understand that the leadership style they use and the level of support they provide, should be tailored to match the needs of those they lead.