Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive congruence or consonance are the terms used to describe when alignment exists between what you think and believe, and what you say and do. When cognitive congruence exists, you will be able to commit fully to whatever task, activity, or relationship you are involved in. This differs from cognitive dissonance which exists when your thoughts, beliefs, speech, and actions are at odds with each other.

Cognitive dissonance tends to occur when you hold two contradictory but related beliefs or cognitions, at the same time and is characterised as the ‘discomfort’ felt due to this misalignment.

Cognitive dissonance is not a disease or illness. It is a psychological condition that can happen to anyone. American psychologist Leon Festinger first developed the concept in the 1950s.

Anecdotally, cognitive dissonance occurs much more frequently than you might imagine, especially when individuals feel compelled to support things they really don’t believe in and disagree with. This can be the case in their work, in law, in religion, or even as part of a group they belong to.

An obvious example of cognitive dissonance is when someone works out to maintain their health, yet smokes cigarettes or drinks alcohol knowing these products pose serious negative health consequences. A less obvious example is someone who wants to save the planet from climate change yet frequently flies to conferences in highly polluting aircraft.

What causes cognitive dissonance?

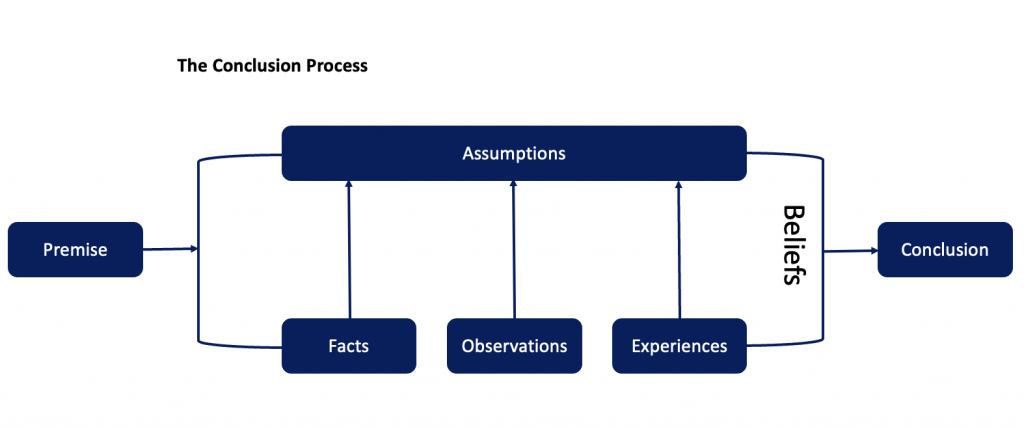

We all have our own values, beliefs, and heuristics, many of which form when we are very young and may be inherited from our parents or learned at school or from our peers. Our experiences, our culture, and even when we grew up all contribute to who we are, what we believe, and how we feel about certain issues. Cognitive dissonance can be caused by the actual or perceived need to act in a way, or agree with an ideology or decision, that does not align with our embedded beliefs or values.

When cognitive dissonance occurs, you feel torn between what you believe and what you have to do or say, and how you have to act. For example, you may be responsible for implementing guidelines or policies you do not believe in, or agree with, due to it being your job, due to peer pressure and group-think, or the fear of the punitive ramifications of speaking out. It could be that you need to abide by policies, rules, and laws, for fear of being punished, losing your job, or in today’s society, being de-platformed or cancelled.

Silently coping with your cognitive dissonance is a burden that can literally drive you to distraction and cause you quite a bit of mental anguish. Keeping your dissenting views bottled up and to yourself allows them to fester and gain weight beyond their metaphoric mass. They can cause you to become tainted, disaffected, and disengaged. They can affect your behaviour and performance and cause you to act out, particularly when your beliefs are being directly challenged and you’re under stress. The turmoil caused by your internal conflict can push you to snap and lash out at the situation, the system, or even an individual.

What can you do to overcome the internal turmoil and discomfort associated with cognitive dissonance?

First, you can acknowledge your feelings and internal conflict. Next, you need to recognise what’s causing the conflict, and why you feel strongly opposed to whatever is causing it. Then you can determine what options are available to you. Ideally, at this stage, it’s wise to fully discuss your dilemma and preferred option(s) with a trusted confidant or possibly even a professional such as a psychologist. You are then best equipped to decide how to deal with your internal struggle.