The Dunning-Kruger Effect

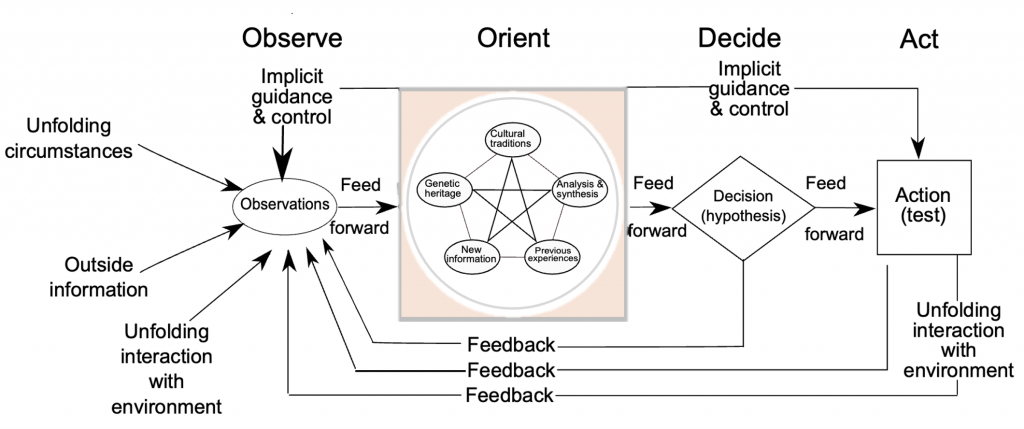

In leadership, confidence is often seen as a cornerstone of success. Leaders are expected to project authority, make tough decisions, and inspire their teams. However, confidence—when misplaced or excessive, can become a significant liability. The Dunning-Kruger Effect, a cognitive bias identified by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999, provides insight into how overconfidence can hinder leadership effectiveness. It suggests that people with limited knowledge in a given area often overestimate their abilities, while those with more expertise are more likely to underestimate themselves.

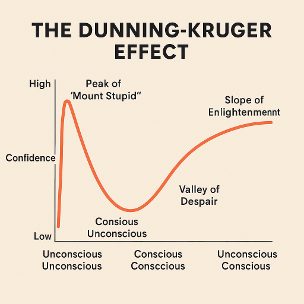

The Dunning-Kruger Effect isn’t just about overconfidence in the early stages of learning. As individuals (and leaders) progress in their knowledge and awareness, they experience a shift in confidence. What starts as overconfidence due to ignorance eventually transforms into a more grounded, and sometimes less confident, phase of self-awareness. This cycle of growth can be framed in terms of the unconscious unconscious, conscious unconscious, conscious conscious, and unconscious conscious, a concept that was introduced by philosopher John Locke in the 17th century, later expanded by Carl Jung and others, to explain how people become aware of what they know, what they don’t know, and the role of self-reflection in personal development.

In this article, we’ll break down the stages of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, explore the psychological concepts behind this phenomenon, and discuss how leaders can navigate their own growth, ultimately leading to more effective leadership.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Stages of Growth and Confidence

The Dunning-Kruger Effect can be broken down into four stages, each representing a different phase in a leader’s journey from ignorance to expertise.

1. The Peak of Mount Stupid: Overconfidence from Ignorance

At the beginning of a leader’s journey, they often exhibit overconfidence despite limited knowledge or expertise in a specific area. This is the first stage of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, where leaders believe they know more than they actually do. Their confidence can be high, and they may make bold decisions without fully understanding the complexity of the task or the potential risks.

For example, a new leader in a company might assume they have a solid grasp on the dynamics of team management and project execution, only to later realize the intricacies and challenges involved. This overconfidence can be dangerous, as it may lead to poor decision-making, arrogance, and failure to seek advice from others who possess more expertise.

In the context of the unconscious unconscious, leaders in this stage are unaware of how much they don’t know. They are confident in their limited knowledge because they are oblivious to the full scope of the subject matter.

2. The Valley of Despair: A Dip in Confidence

As leaders gain more experience and start to learn about the complexities of their role, they begin to realize the depth of their ignorance. This is where the Dunning-Kruger Effect takes a downward turn, and leaders often experience a drop in confidence. They become aware of how much they still don’t know, which can lead to self-doubt, insecurity, and anxiety. This phase is often described as “The Valley of Despair.”

In the conscious unconscious stage, leaders begin to recognize that there is much they don’t understand, but they are still unaware of how to bridge the gap in knowledge. This phase is marked by a lack of confidence and uncertainty about their abilities. However, it is also an important phase of growth. Self-awareness begins to develop as leaders start seeking feedback, advice, and training.

3. The Slope of Enlightenment: Gaining Expertise and Confidence

As leaders continue to learn and gain experience, they start to understand the subject matter at a deeper level. This is when they begin to build genuine expertise, which leads to increased confidence, but this confidence is now rooted in reality, not in ignorance. They understand their limitations and are more equipped to navigate complex situations. They are able to make informed decisions, seek out advice, and recognize when they don’t have all the answers.

In the conscious conscious stage, leaders are fully aware of both their strengths and weaknesses. They recognize what they know and acknowledge what they don’t. This stage is often characterized by humility, as leaders realize that mastery is an ongoing process. Their confidence comes from competence, not overestimation.

4. The Plateau of Sustainability: Balanced Confidence and Continuous Growth

At the final stage of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, leaders have gained a solid understanding of their role, but they also understand that there is always more to learn. This stage is where expertise and confidence balance each other. Leaders are secure in their abilities but are no longer overconfident. They continue to grow and learn, knowing that leadership is an evolving process.

The unconscious conscious stage represents a place where leaders not only know what they know but also have a deep awareness of what they don’t know. This self-awareness allows them to stay open to feedback, adapt to changing circumstances, and guide their teams with confidence and humility.

How the Dunning-Kruger Effect Affects Leadership

The Dunning-Kruger Effect in leadership can have several key implications:

- Overconfidence and Poor Decision-Making: Leaders who overestimate their knowledge may make bold decisions without fully understanding the risks. This can lead to poor outcomes, especially in high-stakes environments. Overconfidence may also cause leaders to ignore advice from more experienced team members.

- Imposter Syndrome in the Learning Process: As leaders become more aware of their limitations, they may experience imposter syndrome, feeling that they are not capable or that they’ve been “found out.” This dip in confidence can make them hesitant to take risks or make decisions.

- Lack of Adaptability: Overconfident leaders may fail to adapt to changing circumstances. They might think their initial approach will always work, even when new information shows that it needs to change. Those in the conscious unconscious stage, on the other hand, are more likely to be adaptable and open to adjusting their strategies.

- Inability to Seek Help: Leaders at the peak of the Dunning-Kruger Effect may fail to seek guidance from more experienced individuals because they don’t recognize their own limitations. This can isolate them from their teams and prevent growth. Leaders who progress through the Dunning-Kruger stages, however, will become more comfortable with asking for help and collaborating with others.

How Leaders Can Avoid the Dunning-Kruger Trap

To avoid the dangers of overconfidence, leaders need to engage in self-reflection and actively seek to recognize their own blind spots. Here are some ways leaders can avoid falling into the Dunning-Kruger trap:

- Practice Humility: As leaders move through the stages of growth, they must remind themselves that there is always more to learn. Humility is essential in the conscious conscious stage, where leaders understand both their strengths and weaknesses.

- Solicit Feedback Regularly: Leaders should seek constructive feedback from peers, subordinates, and mentors to ensure they are aware of their limitations and areas for improvement. This will help them move out of the valley of despair and onto the path of enlightenment.

- Embrace Continuous Learning: Leadership is an ongoing process. Leaders must commit to continuous learning and development, whether through formal training, peer learning, or self-study. This allows them to stay grounded and informed as they grow into their roles.

- Encourage a Growth Mindset in Teams: Leaders should foster a culture that values learning and growth. By encouraging team members to embrace challenges and view failures as opportunities for improvement, leaders can create an environment where the Dunning-Kruger Effect is less likely to take hold.

Conclusion

The Dunning-Kruger Effect highlights the dangers of overconfidence and the importance of self-awareness in leadership. Leaders who fail to recognize their own limitations may make poor decisions, alienate their teams, and stunt their own growth. However, by progressing through the stages of the Dunning-Kruger Effect and embracing continuous learning, leaders can improve their effectiveness, gain true confidence, and lead with greater impact.