Giving Feedback

Giving and receiving feedback is fundamental to the growth and development of us all, but is very often difficult for the giver and confronting for the receiver.

There are many reasons for this. For example, if you’re due for a performance review, you may experience negative emotions and anxiety caused by the fear of being told that your ability, behaviour, or performance isn’t meeting expectations. Inversely, if you need to provide feedback, you may not have the experience or maturity to deal with the effect caused by your feedback, especially if it is likely to be taken badly and you’re not sure how to deliver your message.

Anecdotally, the performance of annual or bi-annual performance reviews alone are totally ineffective. In the weeks leading up to a performance review period, the reviewer will often need to take time out of their normal routine to think back over the past six or twelve months and draft their review notes. Some organisations transfer much of this responsibility to those being reviewed, requiring them to complete templated forms detailing their past achievements and future goals.

There are three key problems with this system:

- It is highly disruptive for the weeks leading up to the reviews.

- It creates anxiety for both the giver and receiver, that for the receiver, may last sometime after the review.

- The goals set tend to focus on hitting targets for revenue or some other KPI, rather than homing in on the underlying behavioural or performance issues that would support the achievement of the desired improvement or change.

Sometimes, people’s pride or ego may prevent them from accepting the feedback, causing them to disengage or even become agitated or angry. If the giver is at all narcissistic, egotistical, or even has feelings of inferiority, they may magnify the severity of the issues or behaviours that constitute the feedback.

Either way, these are common and normal feelings experience during the ‘build up’ to a performance review and they are completely avoidable.

The anxiety sometimes felt by those giving feedback can be alleviated by ensuring proper preparation for the encounter.

We should also remember that not all feedback is negative, and even negative feedback should, in cases were the behaviour or issue is not deliberate or malice, be given in an upbeat, positive manner. The feedback should be seen as identifying the opportunity to improve and do and be better.

A good habit to develop is to record an individual’s positive and negative behaviour and performance in a dedicated notebook. The notebook is then used to recall specific behaviour and performance issues in the lead-up and preparation for the review. Feedback should also be given at the time of the behavioural or performance issue and recorded in the notebook for later review to gauge if the behaviour or performance has improved. A caveat for using a performance notebook is that you need to ensure the book is treated with the utmost confidentiality as it may be used to record sensitive and personal information.

The importance of feedback

Feedback is critical for our development and improvement. We are often too close to our behaviours, traits, and habits to have the proper perspective to see and understand their impact on us, on other’s and on the tasks or work we do.

To change and improve we must first recognise that change is needed, that things could be better, that we could improve. We also need a reason to change, for without a compelling reason, we will not be motivated to action, or disciplined to completion. There are generally only to reasons why people change, and these are to receive a reward or avoid a ramification. By this, I’m not suggesting that giving feedback and inspiring change should employee a carrot or stick mentality. Rather, what I’m saying is for someone to act and make meaningful adjustments that positively change their behaviour or performance, they must see a benefit or disbenefit attach to them making, or not making the change.

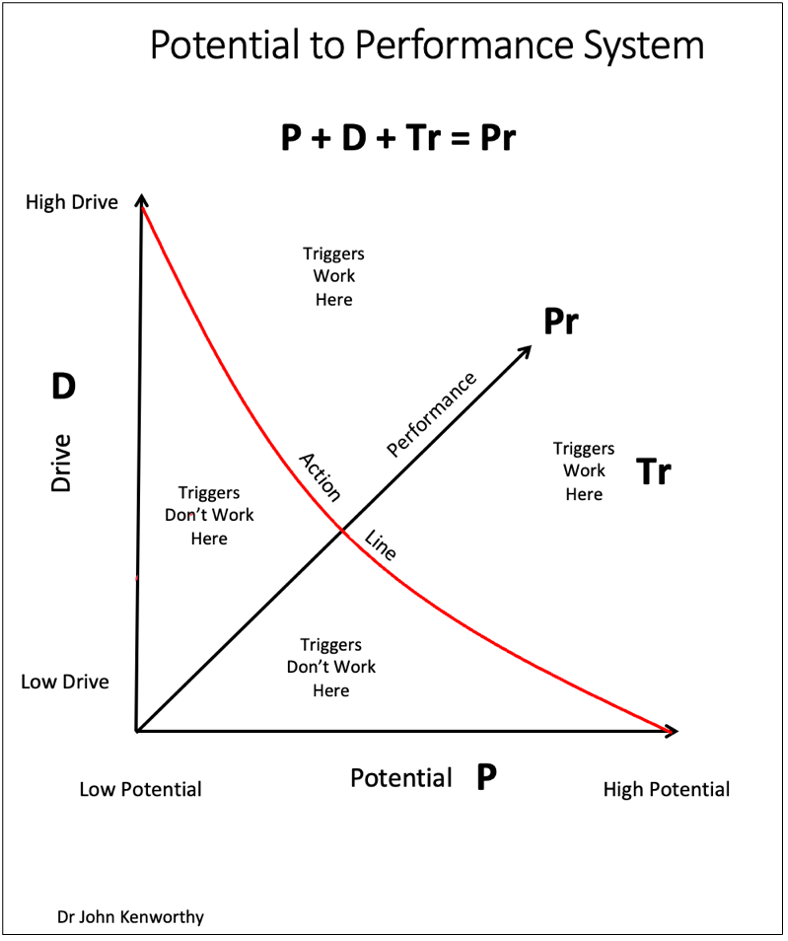

It’s only when we recognise that we have the potential to do or be better and have the drive to achieve the desired future performance level that improvement will occur. It image below shows the relationship between potential and drive on performance. It is entirely possible that an individual who possesses the skills and ability to excel may not, due to a lack of drive or motivation. The inverse is also true for those who want to succeed but lack what it takes at the time. Performance is the coming together of potential and drive and normally requires some form of ‘trigger’ to act as the catalysis for performance. This may be something as subtle as the person’s supervisor engaging with them and letting them know they are doing a great job and see bigger things in their future, to the opportunity to lead an exciting project that could result in a promotion.

The power of feedback is that it can alert us to our blind spots and allow us to consider our behaviour or performance from a different perspective. This is why the best feedback always starts by asking the subject “how do you rate or feel about your performance on…..?”. This allows the giver of the feedback to understand how the subject perceives their performance and therefore allows the feedback to be tailored to address any blind spots or misperceptions.

The giver of the feedback may then continue giving feedback through the process of asking questions that result in the receiver describing how they perceive their performance across multiple performance criteria, steered by the giver and allowing the giver to simply agree or disagree and to explain why.

When giving feedback you must be objective and honest, but this does not mean you should be blunt, brutal, or mean. You should ensure your feedback is CLEAR. CLEAR is an acronym that stands for Context, Language, Examples, Alternatives, Reset, and is explained below:

Context. When giving feedback it is important to provide context and relate the behaviour or performance to whatever negative outcome or result it manifests. This might be telling them that others performance is also impacted, or safety jeopardised, by their behaviour.

Language. How you give your feedback is as important as the feedback itself. Be aware of the receiver’s circumstances and tailor your feedback accordingly. This maybe because the undesirable behaviour or poor performance is due to a situation affecting the subject of your feedback and demonstrating empathy and compassion may be the best way to kickstart the change. Except in specific circumstances where bad behaviour or poor performance is deliberate or done with malice, your language should be inspiring, motivating, and positive.

Examples. It is important to give tangible examples of poor behaviour or low performance. You might say something like “when you do XX, it disrupts others by distracting them from their work, resulting in lost productivity”.

Alternatives. Identifying, establishing, and setting the standard for receivers is necessary. Giving receivers alternatives to their current behaviours or performance provides the direction they may need to make the change.

Reset. Once the feedback has been given, to not harp on about it. Allow the receiver time to absorb the feedback, develop and execute their plan for change, and set realistic review points to check in and gauge their progress. If the plan is not returning the necessary results, help them make adjustments and move on. Don’t forget the plan should be SMART – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timebound.

Remember, the feedback you give is your observation and perception of the receiver’s performance. Never apologise or feel bad about the feedback you give as it is a reflection of the receiver’s behaviour or performance. You are merely raising their awareness of how you, and possibly others view them.

Feedforward

Feedback is retrospective and by virtue of its approach seeks to identify behaviour or performance issues, good or bad, and in the case of bad, to inspire or impose change. The real opportunity is to identify opportunities to coach your followers to continuously improve their behaviours and performance, and consequently their outcomes, rather than waiting for problems to occur. This approach is similar to the lessons learnt process used at the start of new projects. Based on a retrospective or post-mortem performed at the end of another similar project, the lessons learnt process seeks to prevent past problems from occurring in future projects. Similarly, feedforward seeks to head off future behavioural and performance issues by identifying and preventing the formation of bad habits.