What is the best predictor of a person’s likelihood to succeed in just about any endeavour? Is it their confidence, their competence, their grit and determination, or is it their desire, self-belief, or sense of destiny? The answer is, all these factors are important, but the single most significant determinant of their success might just be their personality.

Personality is defined as:

“The combination of characteristics or qualities that form an individual’s distinctive character”.

Your personality reflects who you are. It also determines how you act and react to stimuli and different situations. Some people are open to new ideas and experiences and may readily move away from their existing beliefs or form new beliefs easily when provided with a convincing argument. Others may remain steadfast in their long-held beliefs despite being provided with irrefutable empirical evidence that their presupposition is no longer valid.

While it is impossible to know for sure, anecdotally, most people seem to believe that we all have a mix of traits that are inherent in us and some traits that are more or less prominent based on the situation.

For individuals to be considered to possess specific personality traits, three criteria need to be satisfied. The individual needs to exhibit the specific trait in a consistent manner across different situations and circumstances. This means, for example, that an anxious person will not only respond with trepidation towards a challenging deadline but will respond in a similar way towards a difficult task.

The trait needs to be stable over a long period of time, for example, if the person cries when yelled at in class at school or at home they also cry when they are yelled at elsewhere such as in the workplace.

The individual must also demonstrate unique applications of the trait and not just be following normal behaviour such as responding to aggression with violence or by running away (fight or flight).

Humans have a highly tuned ability to rapidly determine if they ‘like’ or can trust another person based on what is commonly referred to as their ‘first impression’. It is astounding to discover that these first impressions can be formed in 100th of a second and it’s believed that we developed this ability based on our anthropological need to quickly determine if someone is a friend or foe and if they are likely to help or harm us. Each time we observe a person’s behaviour and determine that they’re “talkative,” “quiet,” “active,” or “anxious,” what we are observing is the individual’s personality, the characteristic ways in which the individual differs from other people. Personality and trait psychologists try to describe and understand these differences.

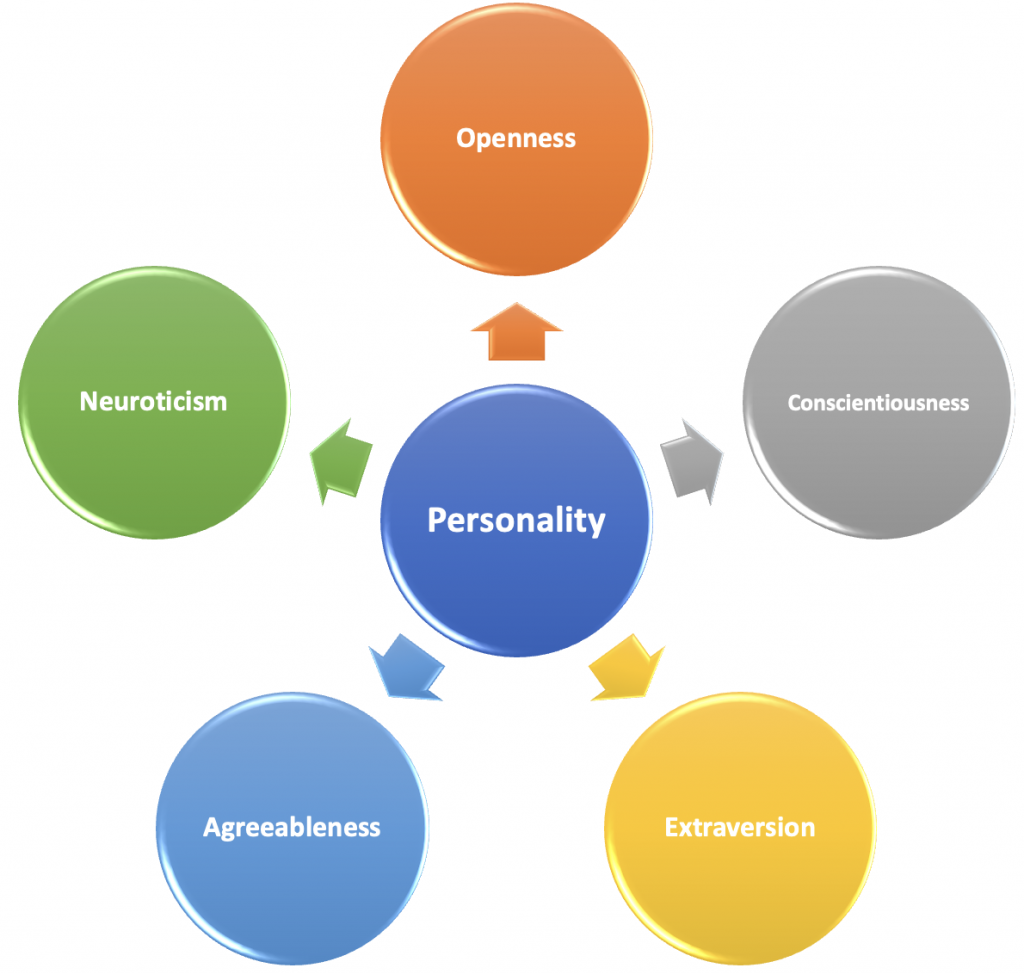

According to trait psychologists, there are a limited number of these dimensions (dimensions like Extraversion, Conscientiousness, or Agreeableness), and each individual falls somewhere on each dimension, meaning that they could be low, medium, or high on any specific trait.

It’s quite common nowadays, that individuals will think of themselves, for example, as either introverts or extroverts in an almost binary way. They believe they are either one or the other all the time, never sway and that these traits are immutable. They think of these traits as precise descriptions of how they behave and that these traits mean the same things for everyone. But research shows that these traits and others are quite variable within individuals and each of us occupy a place on a ‘continuous distribution’ of traits that make us who we are.

In the 1970s two research teams led by Paul Costa and Robert R. McCrae of the National Institutes of Health and Warren Norman and Lewis Goldberg of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and the University of Oregon, respectively, discovered that most human character traits can be described using five dimensions. They surveyed thousands of people and independently identified the five broad traits that are common to most people and can be remembered with the acronym OCEAN: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism.

Openness

People who score high for openness tend to appreciate novelty and are generally creative. At the other end of the scale, people who score low are more conventional in their thinking, prefer routines, and have a pronounced sense of right and wrong.

Extraversion

People who are more extroverted tend to display cheerfulness and initiative and seem more communicative. They are also more companionable, sociable and tend to be able to accomplish what they set out to do. Those with low scores are considered to be introverted, reserved, and more submissive to authority.

Agreeableness

Highly agreeable people tend to be friendly, empathetic, and warm to others, while those less agreeable tend to be shy, suspicious, and egocentric. Whilst being agreeable may help you get along with others, being too agreeable may see you being taken advantage of, and you may find it difficult to say no to others resulting in prioritising their needs ahead of your own.

Conscientiousness

Individuals who are high in conscientiousness tend to be well organised, motivated, disciplined, and trustworthy. Those who lack conscientiousness tend to be irresponsible, easily distracted, and unreliable.

Neuroticism

People who score high for neuroticism are often emotionally unstable. They tend to be anxious, inhibited, moody and less self-assured. Those at the lower end of the neuroticism scale are calm, confident, and contented.

Some examples of behaviours for high and low traits are provided in the table below.

Personality Trait

Example behaviours for low scores

Example behaviours for high scores

Openness

Prefers not to be exposed to alternative moral systems; narrow interests; inartistic; not analytical; down-to-earth.

Enjoys seeing people with new types of haircuts and clothing fashions; curious; imaginative; untraditional.

Conscientiousness

Prefers spur-of-the-moment action to planning; unreliable; hedonistic; careless; lax.

Never late for an appointment or a date; organised; hard working; neat; persevering; punctual; self-disciplined.

Extraversion

Preferring a quite evening to a loud party; sober; aloof; unenthusiastic.

Being the life of the party; active; optimistic; fun-loving; affectionate.

Agreeableness

Quickly and confidently asserts own rights; irritable; manipulative; uncooperative; rude.

Agrees with others about political opinions; good-natured; forgiving; gullible; helpful.

Neuroticism

Not getting irritated by small annoyances; secure; self-satisfied.

Constantly worrying about little things; insecure; hypochondriacal; feeling inadequate.

But what if our understanding of personality traits is wrong and if people don’t act consistently from one situation to the next? This was an assertion that shook the foundation of personality psychology in 1968 when Walter Mischel published a book called Personality and Assessment. Mischel’s assertion was that people behave differently in different situations and that the demonstration of particular personality traits isn’t really that consistent.

Mischel cited that children who cheat on tests at school may strictly follow the rules of a game or may never tell a lie to their parents. Thus, Mischel suggested there may not be any general trait of honesty that links these apparently related behaviours. The debate that followed the publication of Mischel’s book was called the person-situation debate because it pitted the power of personality against the power of situational factors as determinants of the behaviour that people exhibit. The reality may be that, for the most part, individuals tend to act according to their inherent personality traits and under ‘standard’ or normal circumstances; however, are able or even likely to stray from these traits under specific, but inconsistent and undetermined circumstances. However, this does not negate the existence of the Big Five Personality Traits or their validity but does suggest caution and that they are not solely relied upon to determine how someone will behave towards a random situation or how they might if they are afflicted by either internal or external factors.

Understanding the degree to which you possess each of the five personality traits and how they might affect your behaviour especially under certain conditions and circumstances, could help you to stop or pause from reacting, think about your response and take appropriate action for the situation. Further, understanding how these traits affect other people might also allow you to anticipate how other individuals or groups may react to stimuli and how this might have a negative impact on you, especially if you’re their leader.

If you would like to take a free personality test created by Dr John A. Johnson, Professor of Psychology at Penn State University, which is based on the Big Five Personality Traits, please click the button below.