The Role of Leaders in Integrating Technology and AI

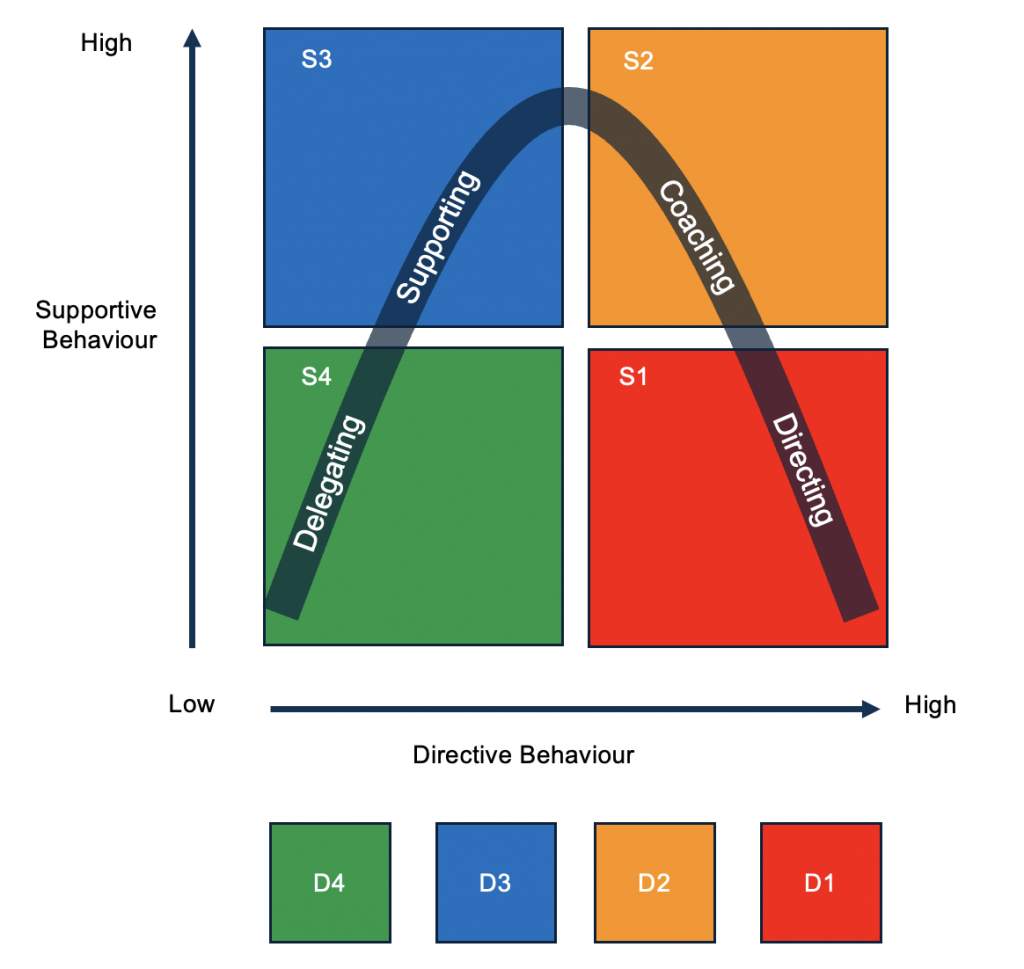

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, the integration of technology and AI is no longer just a competitive advantage—it’s a necessity. However, the key to a successful integration lies in effective leadership. Leaders play a crucial role in ensuring that AI is introduced in a way that empowers staff and drives business growth without causing job losses. Here’s how leaders can navigate this complex transition:

Visionary Leadership

Leaders must have a clear vision of how AI can augment human capabilities and drive business growth. This means not only understanding the potential of AI but also being able to communicate its benefits effectively to the team. A visionary leader sees AI as a tool that can help the organization achieve its goals more efficiently and looks for ways to integrate it seamlessly into the workflow.

Action Points for Leaders:

- Develop a comprehensive AI strategy aligned with business objectives.

- Stay informed about the latest AI trends and advancements.

- Communicate the vision clearly and consistently to all levels of the organization.

Empowerment through Education

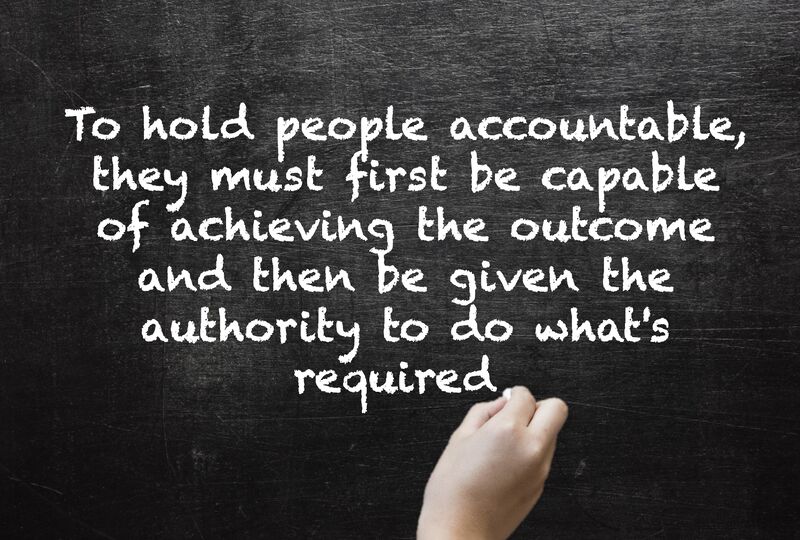

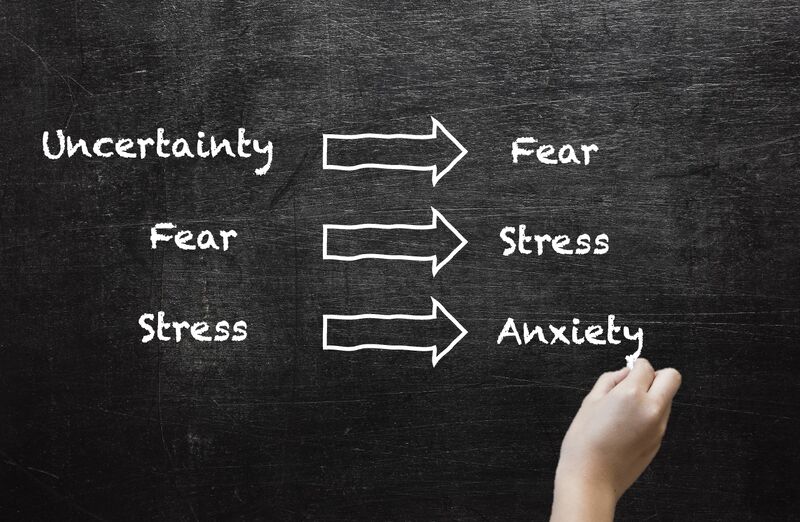

One of the biggest fears employees have about AI is the potential for job displacement. Leaders can mitigate these fears by investing in continuous learning and development. By equipping employees with the necessary skills and knowledge to work alongside AI, leaders ensure that their teams feel confident and capable in this new tech-driven environment.

Action Points for Leaders:

- Implement regular training sessions and workshops on AI and related technologies.

- Encourage a culture of continuous learning and curiosity.

- Provide resources and support for employees to upskill and reskill as needed.

Transparent Communication

Transparency is key when introducing any significant change, and AI is no exception. Leaders need to address concerns about AI and job displacement head-on. By being transparent about the goals and impact of AI, leaders can build trust and alleviate fears. This includes being honest about potential challenges and how the organization plans to address them.

Action Points for Leaders:

- Hold town hall meetings and Q&A sessions to discuss AI integration.

- Create an open forum for employees to express their concerns and suggestions.

- Regularly update the team on AI implementation progress and its impact.

Human-Centric Approach

Leaders should focus on AI applications that enhance human roles rather than replace them. This means prioritizing technologies that automate mundane and repetitive tasks, allowing employees to engage in more creative and strategic activities. A human-centric approach ensures that AI is seen as a partner rather than a threat.

Action Points for Leaders:

- Identify areas where AI can add the most value without replacing human jobs.

- Implement AI tools that assist employees in their daily tasks, improving efficiency and productivity.

- Foster a culture that values human creativity and problem-solving alongside technological innovation.

Inclusive Strategy

Involving employees in the AI integration process is crucial for its success. Their insights and feedback are invaluable in shaping solutions that truly meet the needs of the business and its people. An inclusive strategy ensures that AI is implemented in a way that benefits everyone.

Action Points for Leaders:

- Form cross-functional teams to oversee AI implementation.

- Solicit feedback from employees at all levels to understand their needs and concerns.

- Ensure that AI tools and systems are user-friendly and accessible to all employees.

Ethical Considerations

The implementation of AI should be guided by ethical standards that prioritize fairness, transparency, and the well-being of all stakeholders. Leaders have a responsibility to ensure that AI is used ethically and responsibly, protecting the rights and privacy of employees and customers.

Action Points for Leaders:

- Establish a code of ethics for AI use within the organization.

- Monitor AI systems to ensure they operate fairly and transparently.

- Be proactive in addressing any ethical issues that arise from AI implementation.

Conclusion

By fostering a culture of collaboration, continuous learning, and ethical responsibility, leaders can seamlessly integrate AI into their organizations. This approach transforms potential challenges into opportunities for growth and empowerment. AI, when integrated thoughtfully and ethically, can be a powerful tool that enhances human potential and drives organizational success.